The real purpose of surrealism was not to create a new literary, artistic, or even philosophical movement, but to explode the social order, to transform life itself…. For the first time in my life I’d come into contact with a coherent moral system that, as far as I could tell, had no flaws. It was an aggressive morality based on the complete rejection of existing values. We had other criteria: we exalted passion, mystification, black humor, the insult and the call of the abyss.1

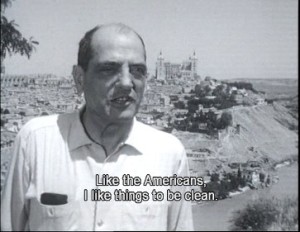

In a 1964 documentary filmed for the French television series “Un Cineast de Notre Temps”, Buñuel’s friend Georges Sadoul tells this anecdote:

His son Juan Luis told me a story that I adore, because it’s Buñuel in a nutshell. He said, “My father had an idea of making a bullet, since he made bullets himself, with such a weak charge that when the bullet was fired at him it would slide of his clothes harmlessly. He worked on it for months, and finally one day he said, ‘I’ve done it!’ To test fire it, he took the precaution of lining up several dictionaries and old phone books. He fired. The bullet went through the target, through the phone books, through the wall and into the neighbor’s!” That’s Buñuel in a nutshell. When he makes a film, he says, ‘I hardly put anything in it,’ and it explodes.

Buñuel accepted his 1972 Acadamy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in disguise. As a young man, he frequently posed as a military officer, and enjoyed roaming the streets with friends decked out as nuns and friars, despite (or perhaps because of) the fact that, in 1920s Spain, impersonating a priest was punishable by five years in prison.

Philosopher:

Your freedom is only a phantom that travels the world in a cloak of fog. You try to grab hold of it, but it will always slip away. All you’ll have left is a dampness on your fingers.2

Mischief:

You can read an account of Buñuel’s final practical joke in this article from The Guardian, appropriately titled Dead man laughing.

Friend:

Jean-Claude Carriere, has a nice remembrance of the great director and their collaboration on Buñuel’s autobiography.

The quotes are from My Last Sigh, by Luis Buñuel & Jean-Claude Carriere, published in 1983. #1 is taken from page 107; #2 from page 109.

(contributed by Inti)

Buñuel’s debut, Un Chien Andalou (1929) was a short film produced in collaboration with Salvador Dalí. This visually arresting series of disturbing scenes (you can watch it

Buñuel’s debut, Un Chien Andalou (1929) was a short film produced in collaboration with Salvador Dalí. This visually arresting series of disturbing scenes (you can watch it